Dairy & Inflammation: What does the evidence suggest?

Hope everyone enjoyed their Fourth of July week celebrations! Below is my response for this weeks Nutritional Biochemistry discussion, where I summarize a review on the influence of dairy products on inflammatory parameters.

Unfortunately the article is not free text, but if you are curious about the publication, it is called “Dairy nutrients and their effect on inflammatory profile in molecular studies” by Da Silva MS & Rudkowska I.

Looking forward to your feedback! Comment your thoughts below!

What is inflammation?

Inflammation is defined as a nonspecific cellular immune response to an injury in attempt to rid the tissues of harmful pathogens, toxins, and foreign material, to avoid the spread of harm to surrounding tissues, and facilitate the rehabilitation of the injured site.1 Redness, pain, heat, and swelling are cardinal signs of inflammation, indicating the onset of vasodilation and phagocyte recruitment from the blood into the interstitial fluid to encourage tissue recovery and repair. Inflammation is a nonspecific defense mechanism in which the body will respond similarly in all scenarios of tissue injury and unwell conditions.1

Inflammation is part of the innate immune system and acts as a bridge to the body’s adaptive immunity. In other words, the body’s innate immunity is first and second line of defense using physical and chemical barriers, as well as internal antimicrobial cell mediators and phagocytes to protect the body from pathogens. Adaptive immunity is called upon by the innate immune system as a specific defense to antigens that enter the body and acts as a memory to protect from those antigens if there is future exposure.1,6

Cytokines are protein hormones that are involved in both innate immunity and adaptive immunity. They are secreted by immune cells to regulate signaling of pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory immune responses.1 There are different kinds of cytokines: interleukins (ILs), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferons (IFNs), and macrophage migration inhibiting factor. Each cytokine is antigen-specific and is produced by different immune cells depending on what is needed to mediate an inflammatory response.1,3

Chemokines are a subclass of cytokines that are also involved in both innate and adaptive immunity. They are secreted and produced by immune cells to recruit leukocytes (white blood cells) to the site of inflammation. The immune cells that are responsible for secreting cytokines and chemokines are macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, eosinophils, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells.3

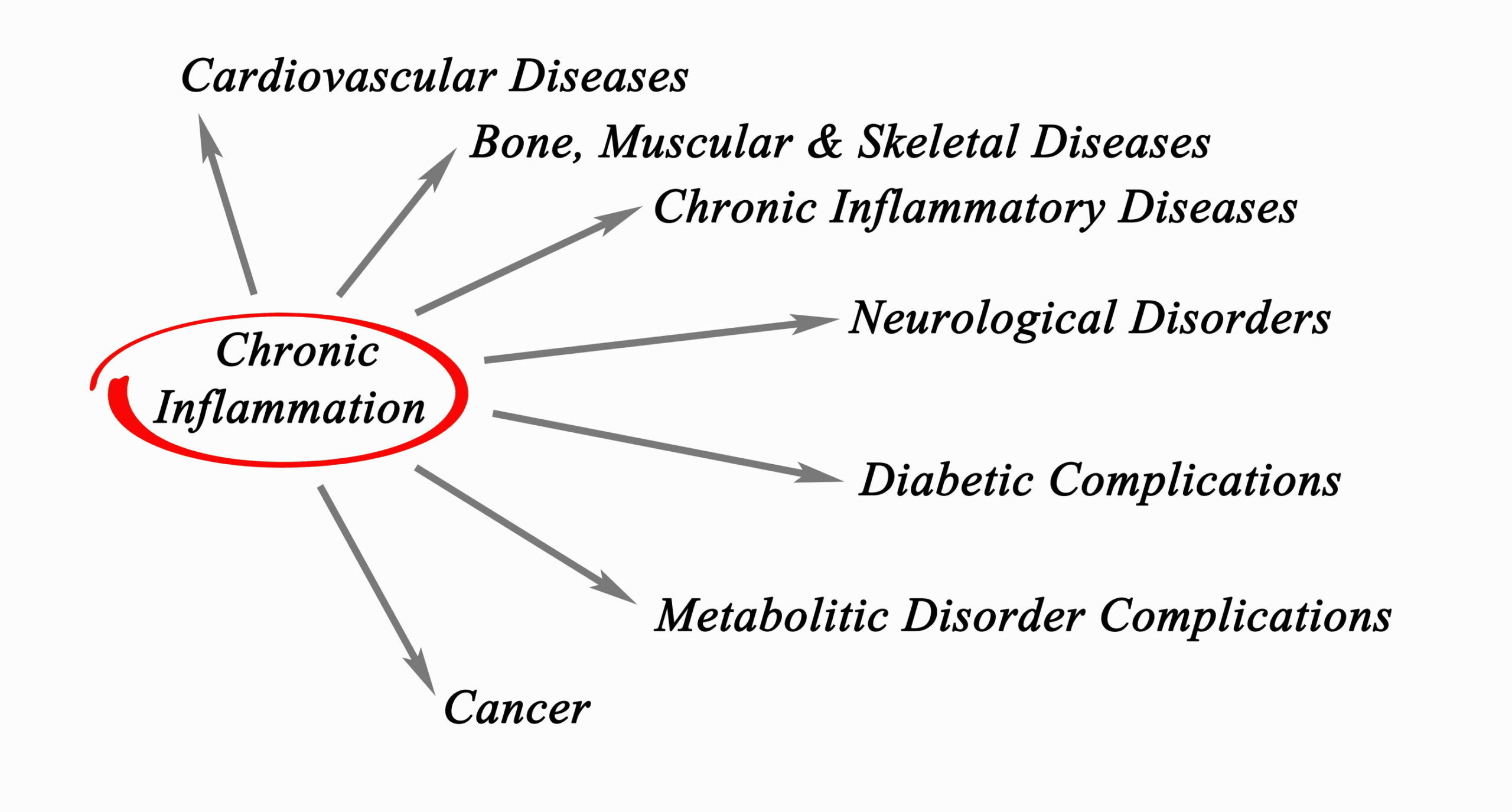

It has been explored in scientific literature that the consumption of dairy products may modulate inflammatory response in humans. Dairy products are diverse sources of nutrients and provide plentiful fatty acids, proteins, vitamins, and minerals that are beneficial for human consumption. However, the individual bioactive substances found in dairy may provoke low-grade systemic inflammation in adipose and vascular endothelial tissues, leading to chronic diseases such as metabolic syndrome, type II diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases.2 In a review of in vitro studies, there is conflicting evidence suggesting that the various biochemicals in dairy individually influence key inflammatory mediators within the body, but comprehensively may not be detrimental.

Fatty Acids

Dairy has a mixed profile of different fatty acids with varied chain lengths: saturated fats, unsaturated fats, and naturally occurring trans-fats. The fat content in milk is primarily composed of saturated fatty acids, which make up 70% of its biochemical structure.2 High dietary intake of saturated fatty acids is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease and is of primary concern when investigating inflammatory response of dairy products. Comparatively, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat sources are cardioprotective, speculating that the mixture of varied fatty acids consumed in dairy may have different effects on inflammatory markers than that of individual biochemicals.2,4

Long-chain saturated fatty acids are associated with the activation of inflammatory markers TNF-A, downregulation of IL-10 (anti-inflammatory), and inactivation in toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in adipocytes. The saturated fatty acid content in dairy, specifically palmitic and stearic acids found in dairy products are individually associated with pro-inflammatory response and increase in disease risk. However, current evidence suggests that the consumption of dairy products reveals an inverse relationship to inflammatory mediators, resulting in decreased IL-6, TNF-A, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1).2 Medium-chain and short-chain saturated fatty acids have shown to decrease cytokine expression or have neutral effects. It is unclear as to the effects of trans-fatty acid content that occurs naturally in dairy.2

Individual fatty acids found in dairy may negatively influence inflammatory response, however consuming a mixture of varied chain fat sources from dairy together may not be detrimental. High-fat versus low-fat dairy products should be of consideration when examining overall nutritional intake.

Vitamins A & D

Dairy is a recognized source of fat-soluble vitamins A and D and are affected by the fat content or fortification status of the product consumed. Vitamin A is pertinent to human growth and thriving but there are no studies that investigate dairy-derived vitamin A on inflammatory parameters.2

The role of vitamin D status on inflammatory markers in humans remains unclear. The activated form of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3), or calcitriol, may have positive influence over inflammatory response and homeostasis of essential micronutrients calcium and phosphorus but is likely dose dependent. Dairy is a recognized source of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, and selenium, however, there is very little evidence that indicates mineral content influence over inflammatory markers.2

Studies have shown decreases in oxidative stress and cytokine expression in adipocytes and endothelial tissue with moderate 1,25(OH)2D3 supplementation. Conversely, higher doses suggest opposite and detrimental results, decreasing adiponectin secretion in adipocytes, and increasing cytokine and chemokine production in human studies, however chronic inflammation may also be associated with vitamin D deficiency.2

Protein

Dairy is composed of casein and whey proteins, giving it a diverse amino acid profile. Individual glycoproteins and amino acids found in casein and whey may also have conflicting influence over pro- and anti-inflammatory properties and have influence of cytokine and NO production in adipocytes and endothelial tissues.

Casein tripeptides have been shown to be hypotensive and influence NO production and monocyte adhesion in inflamed endothelial tissues.2 Alpha-lactalbumin found in whey protein may have conflicting influence over pro-inflammatory response. It has been shown that alpha-lactalbumin downregulated IL-6 and TNF-A production, however, commercial development of alpha-lactalbumin may have opposite effects.2

Dairy is a complete amino acid source and evidence suggests that these amino acids may positive influence the secretion of adiponectin from adipocytes, reduced ICAM-1 expression upregulate NO and IL-10 production in endothelial cells and inhibit cytokine production. Therefore, it is clear that amino acids can influence cytokine production, however it is there is a need for further studies on specific milk-derived amino acids and their effects on inflammation.2

In summary, the biochemical properties of dairy products and their effect on inflammatory parameters in humans remains unclear, however, individual bioactive substances may be detrimental and associated with chronic inflammation. The comprehensive nutrient status of dairy overall may be beneficial due to the synergistic and additive affects of the bioactive substances combined. It may be suggestible that fat content of dairy products should be of primary importance to inflammatory status however, existing evidence does not suggest that either high-fat or low-fat dairy products induce inflammation in human studies. Other factors may have confounding effects on pro-inflammatory influence of saturated fats.8

References:

- Tortora GJ, Derrickson B. Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. 14th ed. Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: 2014.

- Da Silva MS, Rudkowska I. Dairy nutrients and their effect on inflammatory profile in molecular studies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59:1249-1263.

- Lacy P. Editorial: secretion of cytokines and chemokines by innate immune cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:190.

- Neiman DC. Nutritional Assessment. 7th ed. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Iyer SS, Cheng G. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32(1):23–63.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular biology of the cell. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21070/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- Molteni M, Gemma S, Rossetti C. The role of toll-like receptor 4in infectious and noninfectious inflammation. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/mi/2016/6978936/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- Bordoni A, Danesi F, Dardevet D, et al. Dairy products and inflammation: A review of the clinical evidence. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2017 May;57(12):2497-2525.

Comments Off on Dairy & Inflammation: What does the evidence suggest?