Research Paper: Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Hey Everyone! Last semester, I had the opportunity to write two research papers – I wrote both on Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Since they were for two different classes, both offer similar information but presented a bit differently.

I wrote both of these papers during the final two weeks of my contest prep for my WBFF Pro debut in LA. I was under a super ton of stress, but I am still pretty happy with how they came out.

Here is the IBS research paper that I wrote for Pathophysiology of Human Disease course taken Spring 2019.

Irritable bowel syndrome

Stephanie E. Mercurio

University of Bridgeport

Abstract

Objective: To analyze and explore the epidemiology, etiology, risk factors & causation, diagnostic assessment, and current Western & Functional interventions of irritable bowel syndrome, also known as IBS. Methods: Appropriate keyword searches were conducted for the extraction of secondary and tertiary data from existing literature within the previous 5 years to determine the most recent and up to date clinical identification of IBS, related testing, and emerging evidence to develop a functional and evidence-based nutritional protocol for patients diagnosed with IBS by their physician. Results: Irritable bowel syndrome remains a diagnosis without true causation or diagnostic testing for identification and often is diagnosed by medical practitioners as an idiopathic condition. However, there is increasing literature exploring various dietary and supplement protocol that can help alleviate the symptomology of the condition.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, is a chronic digestive condition that affects 25 – 45 million Americans of all ages in the United States.1 IBS is considered a functional gastrointestinal disorder and is oftentimes considered idiopathic. Symptoms include abdominal discomfort and pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits such as constipation, diarrhea, or both. These symptoms must be present for a period of at least 3-6 months and is thought to be a dysfunction of the large intestine.1-2 Gastrointestinal disturbances, such as IBS, are a common reason for patients to be seen by a gastrointestinal specialist. In fact, IBS is cause for up to 50% of patients to visit their gastrointestinal clinic.2 But despite elevated rates of clinical visitation, majority of IBS cases are left without known causation.

Risk Factors & Causation

Irritable bowel syndrome is a chronic and recurring condition that affects people worldwide no matter age, sex, or race. However, women and people younger than 50 years of age are more likely to develop IBS and IBS-related symptoms.8 Although IBS does not lead to disease, it is still a cause of compromised quality of life and creates a negative economic impact on our global health care system.8

Being that majority of irritable bowel syndrome diagnoses are idiopathic, risk factors and causation associated with IBS are very generalized and may also increase a risk for misdiagnosis. It is considered a condition of exclusion, meaning that a physician must exclude other pathologies that have similar symptomology. These include pathogenic infections, parasites, and other more serious conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD.3

Some well-known symptoms of IBS are altered gastrointestinal motility and irregular bowel movements, gut hypersensitivity, mucosal inflammation, interrupted gut flora, intestinal permeability, and allergies to common foods such as wheat, beef, pork, milk, eggs, and lamb.4 These symptoms are also characteristic of other serious gut conditions such as irritable bowel disease, SIBO, Celiac disease, fructose malabsorption, and intestinal permeability.4 Patients who suffer from IBS are often ruled out from having IBD and may be prematurely diagnosed with IBS without being thoroughly evaluated by their physicians for other conditions.

Some experts suggest that IBS is a dysfunction between the gut and brain and change the peristaltic rate of the gastrointestinal tract’s ability to move food along.10 Stress, traumatic life events, and mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, could exacerbate symptomology.10 However, emerging evidence suggests that gut flora may play a greater role in the onset of irritable bowel syndrome. IBS may be onset with events that have the potential of disturbing the microbial balance in our gastrointestinal tract such as antibiotic use, gastroenteritis, inflammation of the mucosa, SIBO, and even implemented probiotics.9

It is hypothesized that SIBO, or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, may be directly related to IBS or that it is a separate condition entirely.9

Assessment

There is no gold standard for diagnosis of IBS, however, evaluation should begin with specific details about patient history.8 There is criterion that have been developed over the years that have helped clinicians increase diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of IBS evaluation. In 1988, a group of experts met in Rome with the goal of generating a symptom-based classification system for the diagnosis of functional gastrointestinal disorders.5 This system was named Rome 1. The definition and symptomatic-criteria have changed over the years, with the most recent iteration, Rome IV released in 2016.5

Rome IV defines IBS as a “functional bowel disorder in which recurrent abdominal pain is associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits”.5

It also categorizes IBS into subtypes:

- IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C)

- IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D)

- IBS with mixed constipation and diarrhea (IBS-M)

Symptoms include bloating and abdominal distention, and should begin occurrence at least 6 months prior to diagnosis, with symptoms also present during the prior 3 months.5 Pain frequency should occur a minimum average of one day per week.5

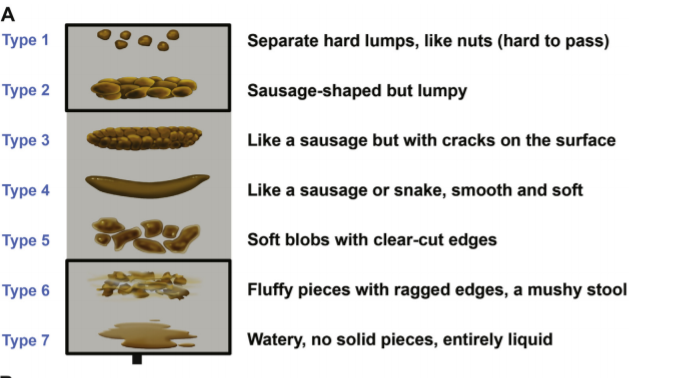

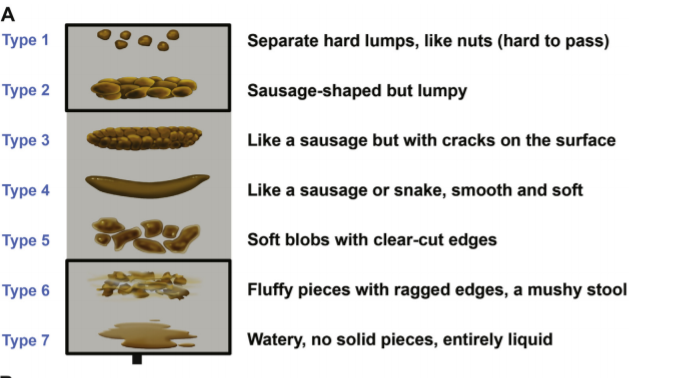

IBS subtypes are determined by completing a 14-day stool diary and comparing results to the Bristol stool form scale, shown in the infographic below.8 Type 1 & Type 2 are associated with IBS-C and Type 6 & Type 7 are associated with IBS-D.5

In addition to Rome IV classification, a physician may investigate a patient’s previous diet, medical, family, and psychological history. A physical examination to identify bloating, gurgling sounds, and abdominal tenderness or pain may be used as well.7 Diagnostic tests like blood work, stool testing, endoscopies, colonoscopies, biopsies, and serologic testing may be used to rule out other digestive disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or colon cancer.4-5

Interventions

Due to the idiopathic nature of IBS, it is common for patients to feel uncertain about diagnosis, or lack thereof. Patients may feel the need to seek the opinions of other healthcare practitioners after initial assessment because they do not feel confident in their diagnosis or the feedback that was received from their specialist.

Regardless of practice, a thorough initial consultation with a patient is important to establish a trusting relationship between patient and practitioner.5 At the beginning of any consultation, the patient should be allowed to tell their story and explain their symptomology as it occurs. The practitioner should recap the information that the patient shares so that the patient feels as though their situation is important and is being regarded as pertinent information in their assessment and diagnosis. All previous diagnostic testing and results should be reviewed by both patient and practitioner.A physical examination should be performed, and if necessary, any remaining diagnostic testing that may be necessary to rule out more serious conditions.4-5

Once these steps have been taken, it is important to convey to the patient that they meet Rome IV criteria for IBS and explain to them what subtype they are likely to have based on their personal and specific symptoms. Once this has been communicated, then an appropriate intervention can be explored and implemented.5

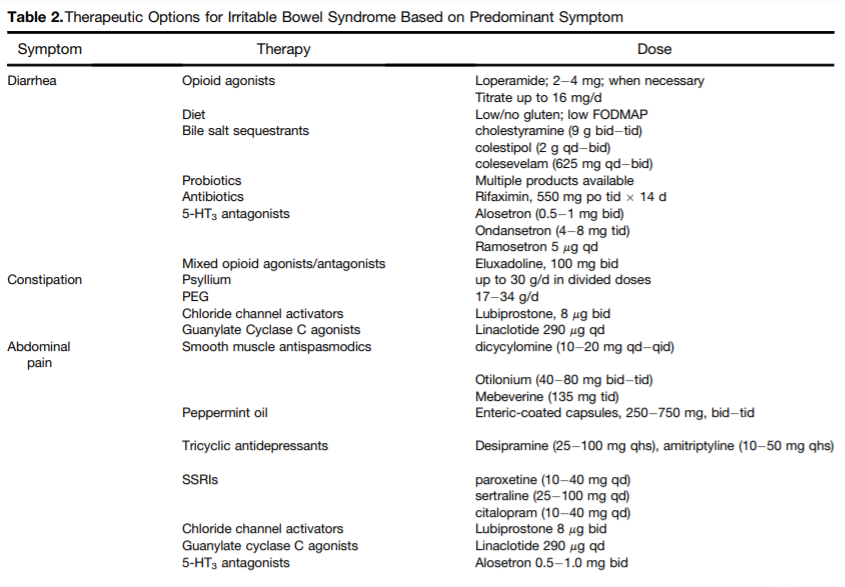

Western medical practitioners will often default to pharmacological interventions depending on the subtype of IBS. For IBS-D, opioid agonists, bile salt sequestrants, antibiotics, and 5-HT3 antagonists will be prescribed to the patient. For IBS-C, a combination of opioid agonists and antagonists may be prescribed, as well as chloride channel activators, Guanylate Cyclase C agonists, and smooth muscle antispasmodics. Tricyclic antidepressants may be used to help relieve abdominal pain associated with IBS.8 Cognitive behavioral therapy to help reduce stress may also be recommended.5 The table below is a comprehensive review of the different types of pharmacological interventions that can be used for IBS therapy based on predominant symptomology.

Increasing dietary fiber is a non-pharmacological intervention that has been scientifically proven to alleviate IBS symptoms across all subtypes.11 It is not uncommon for a medical practitioner to recommend a high-fiber diet to a patient in addition to pharmacological intervention. However, in functional practice, nutrition and lifestyle factors will likely be first line intervention for IBS.

In a recent systematic review, studies showed that overall IBS symptoms improved in all study arms (IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M) with the intervention of soluble fiber in comparison to placebo. These sources of dietary fiber included psyllium, linseeds, acacia, sea tangle, radish, glasswort extract and in some trials, probiotic supplementation.11

Although evidence supports soluble fiber as an effective intervention, there is a need for clinical trials that test specific fiber sources and dosages. Studies testing the efficacy of soluble fiber with IBS patients have used variable amounts from an assortment of different sources.11 Developing main treatment for IBS would require more homogenous data on dosage and fiber type.

Over the past 10 years, FODMAP-restricted diets have been tested for IBS treatment, however, there is some speculation as to the efficacy and safety across all subtypes. There is also a lack of heterogenous data that could help clinicians understand if low FODMAP or FODMAP-restricted diets are effective for all IBS subtypes. In one randomized, single-blinded controlled trial, a small group of 30 IBS patients were categorized into 4 subtypes: IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M, and IBS-U (unsubtyped). When following a 21-day high-FODMAP or FODMAP-restricted diet, with fiber added to the FODMAP-restricted group, there were no significant changes between diets. However, participants with IBS-D in the FODMAP-restricted diet group experienced reduced stool frequency and better scores on King’s Stool Chart.11

In spite of the lack of paralleled study design and homogenous data, FODMAP-restricted dietary interventions seem to have a positive effect on the reduction of IBS symptoms.11 However, FODMAP-restricted diets should be tested for longer periods of time to ensure long-term safety and efficacy as they may reduce total colonic bacterial count and negatively impact colonic health.11 Additionally, FODMAP-restricted diets may be associated with nutritional deficiencies within IBS patients. FODMAP-restricted diets are not synonymous with fiber and are characteristically lower in fiber-rich food sources.

There may be specific nutritional recommendations that clinicians can make that is dependent upon subtype. Patients with IBS-D may respond well to enteric-coated peppermint oil, as it is an antispasmodic and can slow down a hypersensitive gut.4 Peppermint oil contains L-menthol, which blocks calcium channels in the smooth muscle of the GI tract.12 In a recent meta-analysis, peppermint oil has shown a significant reduction in abdominal pain and reduction in the severity of global IBS systems based on Rome criterion.12 For IBS-C, a double-blind, randomized and placebo controlled trial found that colonic transit time and the improvement of defecation was significantly improved adter 8 weeks of supplementation with F. carica paste, which is derived from figs.

The importance of these interventions lays in fact that they are proven to not only be effective, but possibly safer than pharmacological or FODMAP-restricted interventions over longer durations of time.12-13

Conclusion

Irritable bowel syndrome is a complex condition that can be influenced by various factors including diet & lifestyle factors, genetic predisposition, stress, gut dysbiosis, visceral sensitivity, the gut-brain axis, and mediators of metabolic efficiency.12 Although IBS can be found within all walks of life, it is a condition predominantly found in women, under the age of 50 years.12 It can occur after a sudden imbalance in gut function, such as an infection, or have idiopathic causation. Therefore, it is important that when developing an intervention for a patient who presents with IBS symptoms that we apply the principles of evidence-based practice into our protocol.

Step 1: Obtain complete histological profile of the patient including information before and after the time of first symptoms were experienced, the type of symptoms experienced, the regularity of symptoms experienced, previous medical history, family medical history, and any diagnostic testing they may have already had. If further diagnostic testing is needed to rule out more serious conditions, refer out.

Step 2: Use Rome IV criteria to determine IBS subtype. This is important to not only help us understand how to develop and appropriate intervention, but to help us confidently present our diagnosis to the patient and prevent further uncertainty and redundancy is testing.

Step 3: Use subtype to create a nutritional protocol. For a patient with IBS-C, I would remove all laxatives if they are being used, and have the patient try Oxypowder or MagO7 to get things moving. Both supplements function the same and are non-habit forming, unlike over the counter laxatives. It may or may not be necessary to follow the 7-day protocol recommended on the bottle. In addition to the supplement, I would design a low-FODMAP diet for 4-8 weeks, duration depending on the reduction of negative symptoms such as bloating & abdominal pain, and continued constipation. Although fiber sources on a FODMAP-restricted diet are far and few between, I would see how the patient reacted to foods like raspberries, and white/red/golden potatoes with the skin on. If symptoms continue to improve, I would slowly increase soluble fiber intake over time, perhaps a psyllium supplement, oatmeal, or lentils. Some supplements to consider; HCl with pepsin and a comprehensive digestive enzyme that will aid in duodenal macronutrient breakdown and absorption of nutrients. Pancreatic digestive enzymes have shown a reduction in negative IBS symptomology, such as abdominal pain, bloating, and excessive flatulence.15 I would also consider the Ficus carica paste to help increase intestinal peristalsis.

My protocol for IBS-D or IBS-M might differ in that instead of recommending the Ficus carica paste, I would suggest a peppermint oil supplement to help increase intestinal transit time. Perhaps a FODMAP-restricted diet may not be necessary, rather assessing existing dietary fiber intake and adjusting as needed to help add bulk to stools and decrease Bristol Stool Chart scores would be first line intervention. HCl and a comprehensive enzyme would also be supplements that I would recommend for appropriate macronutrient breakdown and absorption.

For intestinal inflammation and possible intestinal permeability, I would recommend supplementing with l-glutamine, which is a conditional amino acid that can become depleted with GI distress, such as IBS and IBD. Glutamine plays an important role in enterocyte health and can help fortify the intestinal lining by promoting enterocyte proliferation and reduction of cell apoptosis.14

There is a need for more studies that can provide us more homogenous data surrounding the efficacy of dietary fiber source and dosage, FODMAP-restricted diet duration, and specific supplementation guides to help support the alleviation of IBS symptoms, which can be debilitating and greatly reduce quality of life. It is apparent that we are just chipping off the tip of the iceberg with gut health and the possible role of our microbiome and intestinal permeability in IBS and IBS related symptomology. There is hope that functional medicinal practice that advocate dietary and lifestyle interventions can prove to be safer and more effective protocols than expensive, pharmacological solutions that address only the symptom, and not heal the root cause of IBS.

References:

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. Facts about IBS. https://www.aboutibs.org/facts-about-ibs.html. Updated November 24, 2016. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- Nanayakkara WS, Skidmore PM, O’Brien L, Wilkinson TJ, Gearry RB. Efficacy of the low FODMAP diet for treating irritable bowel syndrome: the evidence to date. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016; 9:131-142.

- Reisner EG, Reisner HM. Crowley’s an Introduction to Human Disease: Pathology and Physiology Correlations. 10th Ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2017.

- Pizzorno JE, Katzinger J. Clinical Pathophysiology: A Functional Perspective. Coquitlam, BC Canada: Mind Publishing Inc; 2012.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6(11):99.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Diagnosis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/diagnosis. Updated November 2017. Accessed March 26, 2019.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Symptoms & Causes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/symptoms-causes. Updated November 2017. Accessed March 26, 2019.

- Lacey BE, Mearin F, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150:1393-1407.

- https://www.aboutibs.org/gut-bacteria-and-ibs.html. Updated June 01, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Definition & Facts for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/definition-facts. Updated November 2017. Accessed March 26, 2019.

- Alammar N, Wang L, Saberi B, et al. The impact of peppermint oil on the irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of the pooled clinical data. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):21.

- Baek HI, Ha KC, Kim HM, Choi EK, Park EO, Park BH, Yang HJ, Kim MJ, Kang HK, Chae SW. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Ficus carica paste for the management of functional constipation. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016t:25(3):487-496.

- Kim MH, Kim H. The Roles of Glutamine in the Intestine and Its Implication in Intestinal Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5):1051.

- Spagnuolo R, Cosco C, Mancina RM, Ruggiero G, Garieri P, Cosco V, Doldo P. Beta-glucan, inositol and digestive enzymes improve quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017; 21: 102-107.

Comments Off on Research Paper: Irritable Bowel Syndrome